How tropical states and provinces can tackle deforestation and fight climate change

As wildfires rage across Australia and floods batter Indonesia, it’s clear national governments need to do more to tackle the climate crisis. But states and provinces can fight climate change too. In particular, states and provinces have important decision-making authorities they can use to slow tropical deforestation, the second-leading cause of climate change after burning fossil fuels.

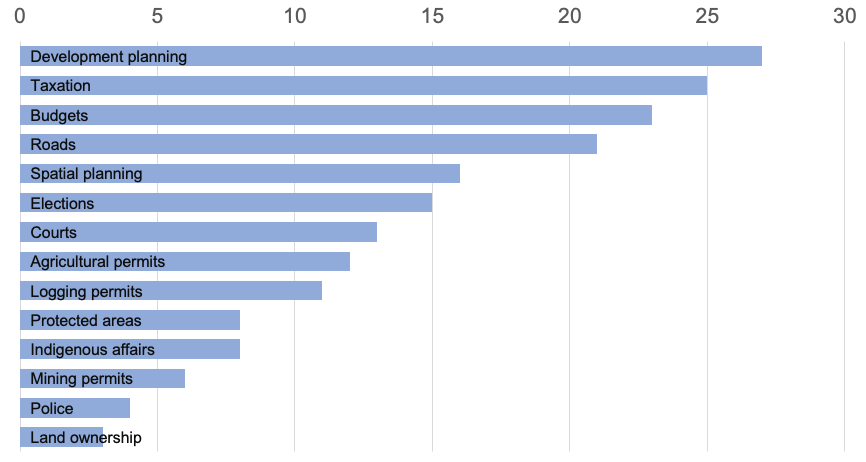

The types of authorities that states and provinces (alternatively termed “sub-national jurisdictions” or “second-tier governments”) can use to influence deforestation most commonly include development planning, taxation, budgeting, and roads. In contrast, states and provinces rarely have authority for land ownership, police, permits for mining, Indigenous affairs, or protected areas, meaning that strategies for reducing deforestation that involve these powers are currently best handled by national governments. States and provinces in Asia have more authority to reduce deforestation on average than states and provinces in Latin America or Africa.

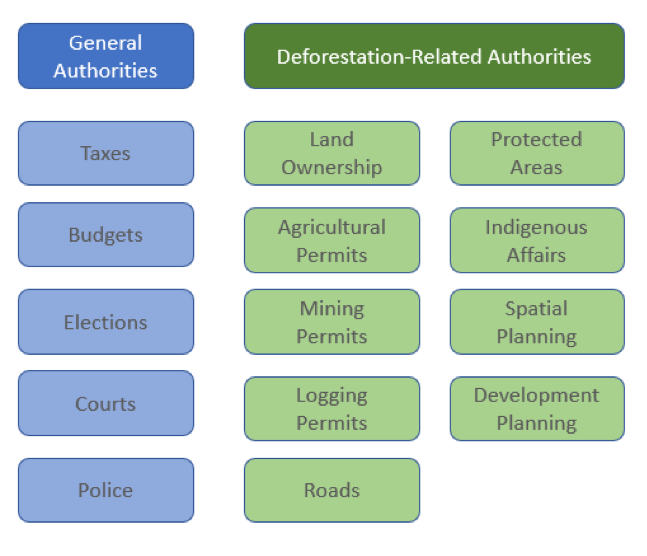

These are among the findings of our recently published paper in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, in which we catalogued 14 authorities states and provinces have to protect forests (Figure 1), across 30 tropical countries with high projected future emissions from deforestation. We have made the data available in a free, open-access database.

Dozens of states and provinces are already taking action on climate change. Forty-nine tropical states and provinces have joined the Under2 Coalition—an international community of sub-national governments committed to keeping global temperature rise below 2°C with efforts to reach 1.5°C. Moreover, 17 subnational governments have endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests—a voluntary declaration to cut forest loss in half by 2020 and strive to end it by 2030. More than 30 states and provinces in eight tropical countries are members of the Governor’s Climate and Forest (GCF) Task Force. Many of those have signed the Rio Branco Declaration, committing their states and provinces to reducing deforestation by 80% by 2020 conditional upon performance-based funding from the international community.

International initiatives to provide financial support for reducing emissions from deforestation (REDD+) have increasingly gravitated toward the state and provincial scale as well. These include the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility’s Carbon Fund; Germany’s REDD Early Movers Program; the California Tropical Forest Standard; and the private Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ Framework.

Here at Earth Innovation Institute we’ve long recognized sub-national jurisdictions as promising laboratories for innovation in public policies, as well as being important in their own right. The largest state, Amazonas in Brazil, is larger than all but 17 countries. We’ve researched how sub-national jurisdictions can transition to sustainable development, and tracked progress through the State of Jurisdictional Sustainability report. Our Tropical Forest Champions initiative promotes partnerships, market access, and investments for states and provinces that protect forests.

The authorities that states and provinces possess most broadly are development planning, taxation, budgeting, and road construction (Figure 2). In 27 of the 30 tropical countries we researched, states and provinces have the authority for development planning. The next-most common authorities are taxation (25/30), budgeting (23/30), and road infrastructure (21/30). This suggests that one of the most important powers states and provinces have is to redirect planned infrastructure development away from forests using their authorities over development planning and roads. While states and provinces often have some authority for taxation, they are often constrained in the kinds of taxes they can levy, and taxes aimed at reducing deforestation are rare in practice. On the other hand, states and provinces have widespread potential to fund local programs to slow deforestation (e.g. through payments for ecosystem services) using their budgeting authority.

States and provinces rarely have authority over mining, policing, or land ownership (Figure 2). State and provincial governments in only 3 out of 30 countries directly own land. It is nearly as uncommon for states and provinces to control their own police (4/30) or to issue permits for mining (6/30). To this end, forest conservation strategies that involve direct land ownership, law enforcement, or mining are most often suited for national governments (see Figure 2).

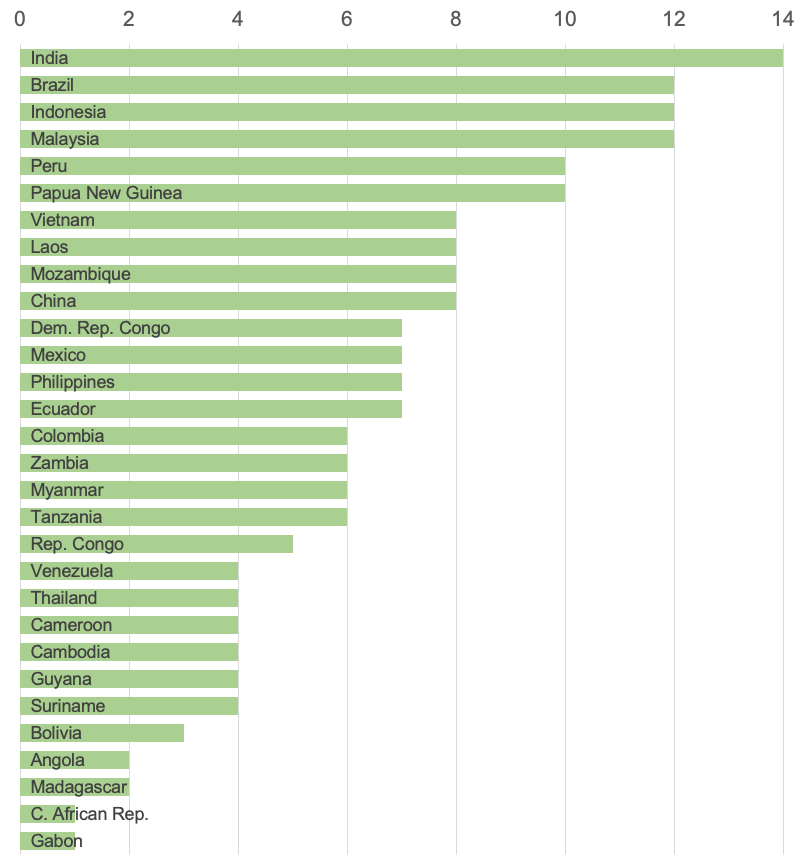

State and provincial governments have the greatest authority to reduce deforestation in India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Malaysia (Figure 3). India is the only country in which state governments have all 14 of the authorities we researched. Three other countries are close behind with 12 authorities: Brazilian states have all authorities except mining permits and Indigenous affairs; Indonesian provinces have all but police and land ownership; and Malaysian states have all but police and courts. In countries such as these, subnational governments have significant scope to reduce deforestation by harnessing these various authorities.

At the other extreme, sub-national governments have the least authority in Gabon, Central African Republic, Angola, and Madagascar (Figure 3). Provinces in Gabon and prefectures in Central African Republic have only one authority—taxation. Provinces in Angola have two authorities—courts and development planning. Regions in Madagascar also have two authorities—elections and development planning. In countries such as these with strong central control, national governments are best positioned to tackle deforestation.

States and provinces participating in prominent international climate and forest initiatives have greater authority. Within the 30 countries that we studied, states and provinces that have joined in the Governor’s Climate and Forest Task Force have an average of 10.3 authorities out of 14. That considerably exceeds the average authority of all second-tier governments in the 30 countries, which is 7.0. Similarly, the states and provinces in the Under2 coalition have 9.1 authorities on average; while the signatories to the New York Declaration on Forests have an average of 9.8 authorities. It is promising that the states and provinces that have made commitments to protecting forests also have greater-than-average wherewithal to do so.

Here’s how we came to our findings. We systematically catalogued 14 indicators of second-tier government authorities across 30 tropical countries that are collectively projected to produce 91% of global emissions from tropical deforestation between 2020 and 2050. Of these 14 indicators, five are general authorities: taxes, budgets, elections, courts, and police. The other nine are deforestation-related authorities: land ownership, agricultural permits, mining permits, logging permits, roads, protected areas, Indigenous affairs, spatial planning, and development planning. For each country, we coded an authority as 1 if second-tier governments possess that authority, in whole or in part. We coded an authority as 0 if it rests with another level of government. We combed many sources of information to assess authorities, including countries’ constitutions, the World Database on Protected Areas, and OECD country profiles on land ownership and planning.

There are caveats. The realities of jurisdictional authority are certainly more complex than can be captured in a binary score. We didn’t account for subnational governments’ institutional capacity, political will, or governance, all of which can bolster or hinder the degree to which they can exercise their authorities. Moreover, we examined the authorities of second-tier governments as they exist on paper (de jure) rather than in practice (de facto). There can be differences between these two at any time, and especially during times of civil unrest or war. Sub-national governments can also influence deforestation through a variety of channels aside from their direct authorities. They can convene stakeholders, and exert upward political pressure on national governments, for example.

The authority of second-tier governments is by no means the only important information to consider in reducing emissions from deforestation. Although our research results can help international initiatives to reduce emissions from deforestation (REDD+) prioritize support across subnational governments, it should be coupled with deeper country-specific analysis. This can include information on regional politics, the history surrounding land use, and the values of local decision-makers. It should also consider other stakeholders outside of governments, including Indigenous peoples and local communities, private companies, and non-governmental organizations.

The bottom line: Second-tier governments are unlikely to be able to solve climate change on their own, but they can play an important role. Our paper can help, by showing which powers second-tier governments have the potential to use to reduce tropical deforestation.

Related:

The State of Jurisdictional Sustainability: Synthesis for Practitioners and Policymakers

In many countries, natural climate solutions can be the biggest climate solutions