The big opportunity to conserve tropical forests that didn’t get enough attention

While the world struggles to combat the Covid-19 pandemic and all of its economic and social consequences, the climate crisis continues to grow in its severity. Tropical forests are potentially an important part of a global climate change solution: they contribute roughly 10% of global emissions but could provide 20% or more of the emissions reductions needed by 2030 to prevent catastrophic climate change. However, global strategies to conserve tropical forests are not delivering the results needed; the years of greatest tropical forest loss since 2000 have been the last four. The effects of the pandemic are likely to fuel this disturbing trend as more people turn to forests to farm, raise livestock, and extract resources from forests to survive.

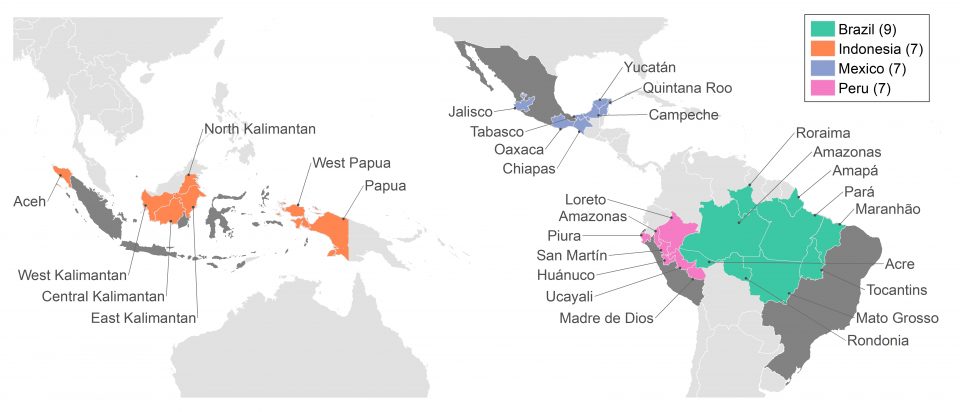

But this moment also presents an important opportunity to adjust tropical forest protection strategies. In 2014, 13 subnational governments signed the Rio Branco Declaration (RBD), committing to reducing deforestation within their respective borders by 80% or more by the end of 2020. They also outlined the support they would need from international donor governments, investors, supply chain actors, and others: (a) adequate, long-term performance-based funding; (b) private sector partnerships; and (c) the establishment of simple, robust performance metrics. By 2018, the RBD had 38 signatories, subnational governments poised to slow the loss and speed the recovery of forests at scale. In a new paper, we analyzed the progress of 30 of these states and provinces (or jurisdictions) towards the deforestation reduction target.

Are the RBD signatories on track to achieve their goal?

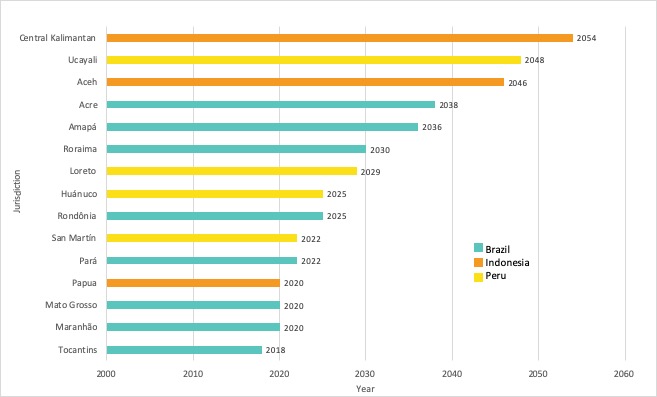

Our analysis showed that half of the jurisdictions (15 states and provinces) made progress toward the target of reducing deforestation by 80%. Of these, more than half are in Brazil and the remainder are in Peru and Indonesia. We estimated that three Brazilian states and one Indonesian province may still achieve the RBD target by the end of 2020, assuming that the deforestation trends from previous years are maintained. However, Brazil faces a new political reality that is credited with contributing to increased deforestation and forest degradation, and is likely to intensify the 2020 fire season relative to 2019.

We found that progress towards the RBD goal was not necessarily tied to whether or not a jurisdiction had established a similar target within its own policy framework. However, the country in which a jurisdiction is located, and that country’s history of establishing deforestation targets, does seem to play a role. Specifically, Brazilian jurisdictions tend to be further along, largely because the RBD itself was modeled on existing Brazilian targets.

Additionally, jurisdictions’ reference levels (against which annual deforestation rates are measured, and are often based on deforestation rates over some period of time in the recent past) influence relative progress towards the goal. For example, West Papua (Indonesia) and Madre de Dios (Peru) have historically had low deforestation rates, but are now clearing more forest, well above the historical average and are thus far off the mark in achieving the RBD target. Conversely, Mato Grosso and Pará (Brazil) have historically deforested large areas and are now making reductions well below the historical average.

What support did jurisdictions receive to achieve their commitment to reduce deforestation?

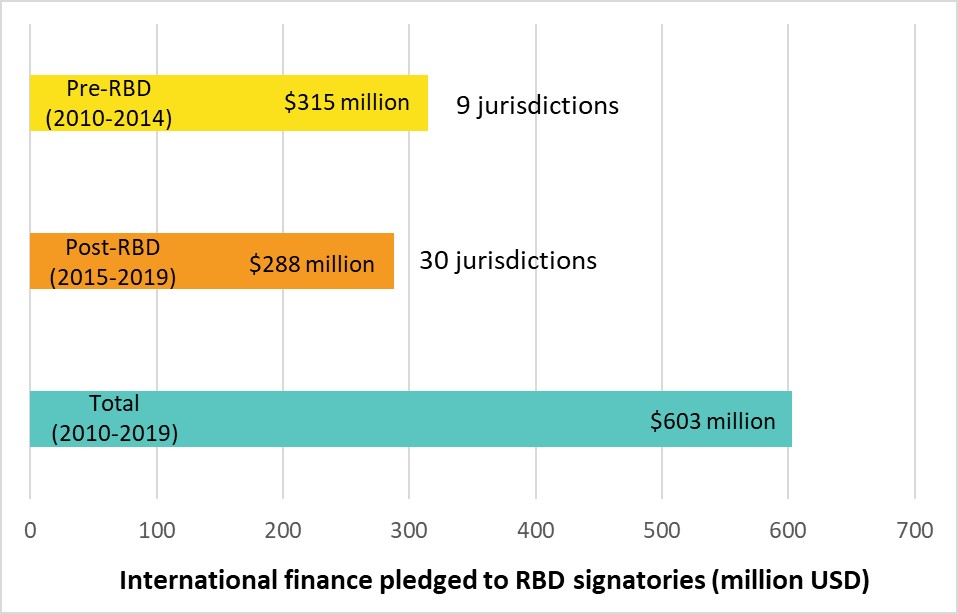

Despite RBD signatories’ clear indication of the types of support they would need, the response from the international community was muted. Only one new commitment of funding was pledged as a direct response: Norway’s pledge to members of the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force (GCF TF), a collaboration of states and provinces working to protect tropical forests. While this pledge increased the number of jurisdictions receiving funding pledges (from 9 to 30), the overall pot of money going to jurisdictions for deforestation-reduction actions did not increase as a result of the RBD. Thus, although many more jurisdictions received at least a small incentive to reduce deforestation, all likely received far less than necessary to achieve the goal. We found that most of the jurisdictions making progress toward achieving the target also received substantially more funding pledges before the RBD was declared than those making minimal or no progress. Very little of the pledged finance is in the form of performance-based finance; only two states (Acre and Mato Grosso, in Brazil) were direct recipients of REDD+ Early Movers funds and no other performance-based finance was pledged.

The private sector’s response to the call for partnerships was minimal, as well. As we described in our report on the “State of Jurisdictional Sustainability”, just over one-third (11) of the study jurisdictions have established “declared” partnerships, in which a company has formally joined a declaration, coalition, or jurisdictional governance structure, but which has not yet resulted in formal preferential sourcing, financial investment, or technical assistance to the jurisdiction. Of those declared partnerships, only five have been “contracted,” with a formal agreement defining the responsibilities and contributions of each party.

What does this mean for global climate change goals?

We estimate that, if current deforestation trajectories continue, the RBD signatories in our study could contribute approximately 3.7% (0.65 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent [GtCO2e]) of the greenhouse gas emissions reductions needed to keep global warming at 1.5°C, compared with a potential 5.7% (0.98 GtCO2e) if they were to all meet the RBD target.

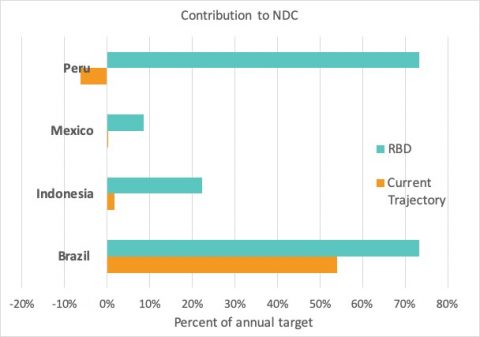

We also estimated the potential contribution of the 30 RBD signatories in our study to achieving their countries’ climate goals under the Paris Agreement. We found that the Brazilian states could have contributed over 70% of Brazil’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) (nearly 863 million tons CO2e [MtCO2e] in annual emissions reductions) by 2030 if the states were to achieve the RBD target. However, if current levels of deforestation hold, we estimate that Brazilian states would account for 54% of Brazil’s NDC emissions reduction target – nearly 20% less than if they fully met the RBD target. Peru offers a more dramatic case: if all seven Peruvian Amazon RBD signatories were to achieve the RBD target, they would contribute nearly three-quarters of Peru’s NDC goal. Unfortunately, however, deforestation rates in half of Peruvian Amazon jurisdictions are rising. Collectively, they are on a trajectory to increase emissions from deforestation, adding 3.68 MtCO2e annually which will need to be compensated by other sectors in order for Peru to achieve its NDC goal.

What kinds of support do subnational jurisdictions need to reduce deforestation going forward?

Given the severe social and economic impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, subnational governments need more substantial support to implement comprehensive low-emission development strategies, many of which are incorporating “green recovery” concepts:

- Greater, more sustained and more creative support from the international community. Our analysis shows that international finance is sorely lacking, and that the jurisdictions and countries that are making progress in reducing deforestation are doing so despite this lack of support. Building the political will and institutional capacity to lower deforestation rates requires major effort over a sustained period of time. Faster and larger responses on behalf of the international community to calls for help from the governments of tropical forest jurisdictions could potentially contribute significantly to greater success in slowing deforestation in the coming years. However, this will likely require financing and other support beyond that which bilateral, multilateral, and other donors are able to deliver as a result of their current priorities and restrictions.

- Greater financial and technical support from the private sector. A number of companies have made commitments related to sustainable sourcing of forest commodities, sometimes including specific “zero-deforestation” commitments. Very few, however, have reported quantitative progress on those commitments. An important missing piece of the puzzle seems to be effective partnerships between the private sector and jurisdictions that are pursuing sustainable, equitable development across their entire jurisdictions. Each needs the other to follow through on its respective commitments. This is the central goal of EII’s Tropical Forest Champions initiative.

- Recognition and rewards. Subnational governments that commit to forest-friendly development need to receive recognition and rewards if they are to translate aspiration into impact. Initiatives that link finance to verified results (“pay-for-performance”) can serve as rewards for territory-wide progress, and as incentives for poor-performing jurisdictions to improve. They (and the companies that partner with them) also need publicity for their forest-friendly strategies and programs, to attract investors and buyers of their products and to engage international donors.

2020 was set to be a defining year for forests and climate. It marks five years since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, when signatory countries are expected to submit new or updated NDCs outlining their emissions reduction targets. It also marks a milestone year for several goals of the New York Declaration on Forests, and the target year for the RBD and several private sector commitments. Despite the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic and all the chaos it has wrought, 2020 could also mark a turning point for the global response to forests and climate change if donors and investors capitalize on the opportunity to support and partner with tropical forest jurisdictions.