Can Europe stop tropical deforestation?

Reversing tropical forest loss, which pumps nearly one tenth of all human-caused carbon pollution into the atmosphere each year, is essential if the world is to avoid the most dangerous climate change impacts. Achieving that goal requires far more support for tropical forest regions.

Upcoming decisions by the United Kingdom and the EU on slowing deforestation linked to international supply chains could deliver that support.

Tropical deforestation is a formidable challenge. Across the tropics, hundreds of millions of people decide each year that it is in their best interest to cut down forests, weighing short-term food security and economic considerations that COVID-19 has made even more pressing.

Tropical forest nations are following in the path of developed nations, where most forestland suitable for farming was cleared centuries ago.

Now the developed world is asking tropical forest nations to do what it never did—keep their forests standing. But as long as the benefits to tropical societies of forest clearing remain more certain, forests will continue to fall at an alarming rate.

In the Brazilian Amazon, a hectare of land suitable for agriculture is worth about $400 forested and $1,400 (or more) cleared. Clearing that hectare releases 500 tons of CO2, and—considering the social costs of climate change as defined by the US EPA—impacts all of us to the tune of $50,000!

Surprisingly, a global system that rewards farmers, communities and entire regions for protecting their forests does not exist. And as a result, political leaders ready to move down the path of forest-friendly development are not getting the help they need.

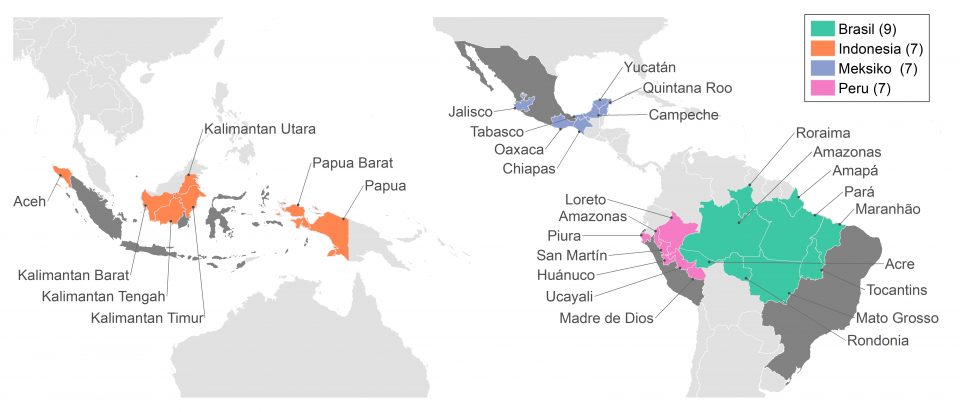

Our colleagues recently assessed 30 tropical forest states and provinces that promised years ago to lower deforestation 80% by 2020 if they received adequate funding and corporate partnerships. When extended into the future, these combined commitments would deliver 11% of the global emissions reductions needed by 2030 to keep us within the 1.5°C goal of the Paris agreement, avoiding more than a trillion USD in economic damages.

Aside from an important $25 million contribution from Norway, this remarkable opportunity to slow deforestation was met with silence.

These regions should be the centerpiece of the UK & EU strategy for slowing and reversing tropical deforestation. They are ready to make progress, but they need help.

Fortunately, key pieces are in place for delivering that help.

First is the rapidly expanding market for forest carbon offsets. Hundreds of companies are pledging to go carbon neutral and have shown interest in buying offsets to help them achieve their goal.

Forest carbon offset projects in the tropics, however, usually have little or no connection with the government policies and programs needed to slow deforestation across vast regions. A new type of “jurisdictional” forest carbon offset will soon be available that establishes links to policy and guarantees indigenous peoples and other local communities a seat at the table.

Mato Grosso, Brazil’s biggest agricultural producer and the Amazon state that has reduced deforestation the most in the last 16 years, could be the first to offer these “jurisdictional” forest carbon offsets. Other tropical forest states and provinces are keenly interested in doing the same, but lack the financial and technical support needed to meet the rigorous requirements.

International climate finance is set up to reward the end goal—declines in emissions from deforestation. Finance for helping jurisdictions reach that end goal is “too slow and too low.”

The growing demand for forest carbon offsets could fill this gap through a “pre-verification” mechanism by which companies invest directly in low-carbon enterprises, farm systems or indigenous peoples’ programs with the promise of a proportional share of future offsets. The UK and other donors could provide capital that makes these investments less risky.

Tropical forest governors who choose forest-friendly development also need partnerships with companies, more than 500 of which have committed to remove deforestation from their supply chains. Companies have been reluctant to meet their pledges through participation in jurisdictional strategies; only 5 of 39 jurisdictions we assessed had established such partnerships.

Companies say they fear such collaborations will expose them to farmers or businesses engaged in deforestation, opening them to attacks from environmental advocacy groups that have led the charge on boycotts and divestment strategies for slowing deforestation.

What we need now is to go beyond the focus on boycotts and divestment to push companies and investors to partner with farm sectors, businesses and governments aspiring to achieve forest-friendly development. Companies that do their part to support this progress could be made more competitive through the UK and EU policy frameworks under development for removing “imported deforestation” from commodity imports.

We have just completed a decade where more finance and attention has been paid to protecting tropical forests than ever before, but they are continuing to fall at dangerously high rates. It is time for a course correction—to meet societies of tropical forest regions where they are, instead of where developed nations want them to be.

The UK and EU, as major donors of forest protection efforts and the UK, as host of the 2021 climate summit in Glasgow, are strategically positioned to lead this important shift.

This op-ed was originally published by Business Green.